THE CLOCK IS TICKING

As climate change intensifies, perhaps no place in the United States is more vulnerable than New York City.

Time left to prevent irreversible damage from climate change.

Day(s)

:

Hour(s)

:

Minute(s)

:

Second(s)

By Charlie May

New York faces unique threats because of its coastal geographic location as well as its dense population. The threats posed by climate change include rising sea levels, increased precipitation, massive flooding, extreme heat waves, coastal storms and more.

Sea levels in New York City have risen a foot since 1900, primarily because of expansion of warming ocean water, according to the Department of Environmental Conservation. Scientists have projected that by the year 2100, sea levels along the city’s coastlines could be 18 to 50 inches higher than today. Average temperatures on the hottest days of the summer have increased at rates ranging from .01 to .07 degrees per decade, depending where measurements are taken in the five boroughs.

The power to enact major changes, such as imposing a carbon tax nationwide or banning the burning of coal or setting vehicle emission standards, largely rests in Washington. The failure of national leaders to take any significant action has left New York City largely on its own.

NYC C02 Emissions by Sector (2016, in tons)

While some argue that New York City must be more aggressive, given the lack of action or urgency from Washington, there are blueprints in place to make necessary and historic changes.

Starting in 2005 under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city began to take important steps to reduce the city’s carbon footprint and prepare for the worst effects of climate change. Those policies have continued under Mayor Bill de Blasio.

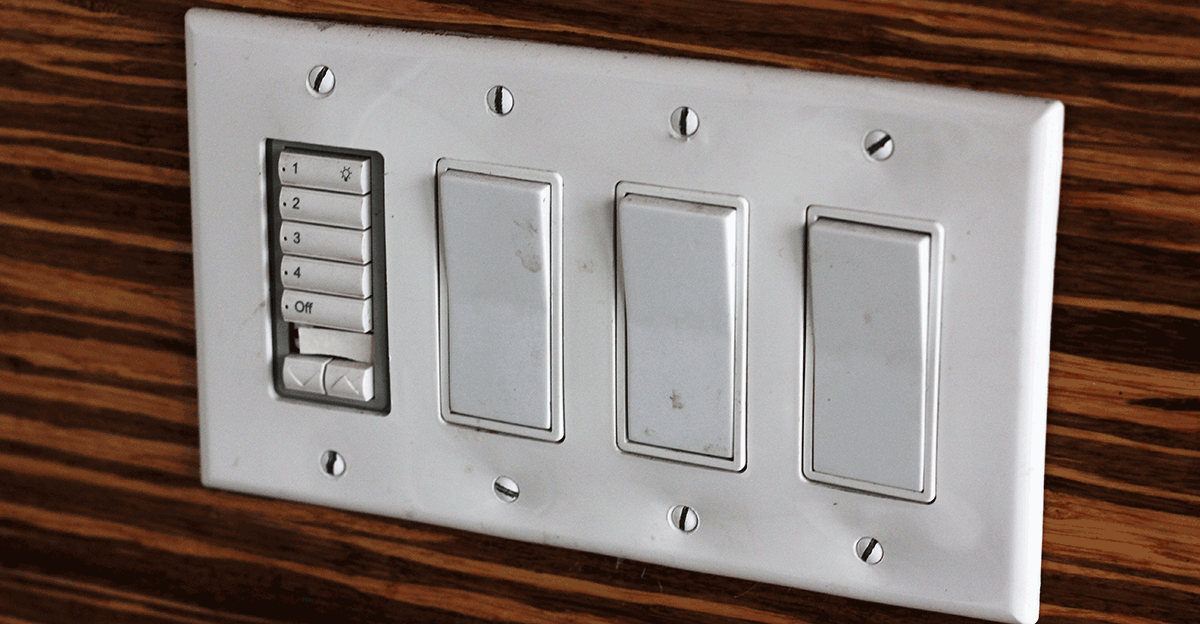

In April, the New York City Council passed the Climate Mobilization Act. The most far-reaching provision would require buildings over 25,000 square feet to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. To comply, most large buildings in the city would have to make major investments to retrofit windows, insulation and heating systems.

The package also mandates that many residential and commercial buildings be equipped with solar panels, a green roof or wind turbines; it requires the city to assess replacing its 24 gas-fired power plants with renewable energy sources and batteries and establishes a renewable energy loan program for building owners.

Dirty Buildings

In New York City, buildings account for 67 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and are by far the leading contributors to the city’s carbon footprint because of the amount of fossil fuel energy they use. The bills included in the Climate Mobilization Act take huge strides to reduce those emissions and issue hefty fines to buildings that don’t comply.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions By Use

For buildings greater than 50,000 square feet

But the legislative package was staunchly opposed by the real estate industry, which argued that these changes would drive up residential and commercial rents to cover the costs of changes buildings must make. Those costs could exceed $4 billion but should be offset by lower operating costs to building owners, according to The New York Times.

New York City’s greenhouse gas emissions have decreased by nearly 15 percent since 2005, according to the Inventory of New York City Greenhouse Gas Emissions, a report published by the Office of the Mayor in 2017. In 2015, the city’s greenhouse gas emissions per capita were an average of 6.1 metric tons of carbon dioxide, far lower than the nation’s average of 19 metric tons of carbon per capita, the report stated.

The Politics of Climate Change

Climate activists are buoyed by New York’s recent actions and hope they indicate a groundswell for a more aggressive approach nationally, despite the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, which pledges international action and cooperation to fight climate change.

In Washington, it’s not real estate interests that are opposing legislative solutions to climate change. Since 2008, the oil and gas industries have spent at least $125 million per year to lobby members of Congress, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. To date, they have succeeded in blocking efforts to impose a carbon tax to decrease carbon emissions, and in loosening regulations on oil and gas drilling and on automobile emissions.

New York’s biggest contribution to climate action on the national stage might be sending Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Washington. There, she has championed legislation that ties climate initiatives like imposition of a carbon tax to a variety of health and economic justice measures. She and her Green New Deal have gotten a lot of attention and brought climate change into the national spotlight.

The Task at Hand

Back in New York, while the city has better positioned itself to be an urban leader in enacting policies aimed to help mitigate climate disasters, implementing sometimes controversial plans to make the city more resilient will require making citizens ever more aware of the stakes and the difficult choices ahead.

When the city’s OneNYC task force on climate change asked 14,000 New Yorkers last year to rate the major challenges facing the city, only 19 percent cited climate change. Many more people cited housing, health and education.

Most New Yorkers don’t rate climate change as a priority

Citizen commitment has already have been tested as the city has studied a range of ways to deter flooding throughout the lower stretches of Manhattan. Installing underwater gates to hold back storm surges, raising the East River Park by 10 feet, pushing back the shoreline with berms from landfill, installing less than attractive sandbags along lower stretches of the East River — all have been proposed and have been opposed by groups of residents.

While Hurricane Sandy in 2012 was a wakeup call for all New Yorkers, exposing widespread vulnerabilities in its power grid, transportation networks, sewage and water systems, it’s difficult to maintain that sense of alarm over time.

But New York’s younger residents, who will face the consequences of putting off action and hard choices today, have jumped into the battle in significant numbers, using protests, education, lobbying tactics and the ballot box. Shunning the incremental tactics of older environmental groups, many young people feel this will be their generation’s defining cause, like Vietnam.

It’s a race against time, and a time of raising voices. The stories in this project explore the risks New York City dwellers face through heat waves, flooding and infrastructure collapse if the city loses this race; examine how youth movements have sprouted to carry the torch for climate change; and considers some innovative ideas that have been adopted in New York in the quest to make a green future possible for everyone.

Flooded Runways & Clogged Sewers

As climate change takes its course, the city will face major challenges to protect its critical infrastructure from rising sea levels.

Dead Heat

Longer, hotter, and more frequent heat waves will require more drastic mitigation efforts from city officials. The higher temperatures put the most vulnerable at greater risk.

Waterfront Woes

Coastal New Yorkers are in big trouble as the city’s sea levels continue to rise, threatening the place they call home.

By Gaspard Le Dem

Since Hurricane Sandy, city officials have sunk billions of dollars — with mixed success — into megaprojects to keep vulnerable coastal neighborhoods safe from the possibility of another catastrophic weather event.

The mayor’s latest proposal to safeguard Lower Manhattan from another hurricane by extending the southern tip of the island into the Hudson River is expected to make a whopping $10 billion dent in city coffers.

But scientists say that while extreme weather will increase with climate change, the problem goes far beyond the occasional superstorm.

Experts say that officials may be overlooking the longer-term threat rising sea levels pose to nearly everything that makes the city run — from its subways to its sewage and water systems, its airports and electric grid.

Sea level has risen a foot around the five boroughs since 1900. Levels are expected to rise another 6.75 feet by 2080 and 9 feet by 2100, according to worst-case estimates from a March 2019 report by the New York City Panel on Climate Change.

“This is not something that happens during a storm, this is a longer-term, pervasive threat of sea-level rise in all of its forms,” said Robert Freudenberg, vice-president of energy and environment at the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit planning organization that focuses on sustainable development in the tristate area.

The association estimates that by 2150, critical regional infrastructure such as power plants, wastewater treatment plants, LaGuardia airport and low-lying rail lines could be permanently flooded by rising sea levels.

Here’s a breakdown of some of the biggest challenges New York City faces as it comes closer and closer to the water’s edge.

NYC’s Sewer System Could Soon Be Seriously Backed Up

The underground network of pipes that keeps New York City’s streets flood-free will need major updates to avoid getting backed up because of rising sea levels, experts say.

When the city’s wastewater treatment plants reach capacity — after heavy rain or snowmelt, for example — any water that can’t be treated is released into the Hudson River or Atlantic Ocean through large pipes called combined sewer outfalls.

Source: New York City Department of Environmental Protection

Today, those uber-pipes lie well-above sea level. But as sea levels continue to rise, they will increasingly be under water, especially at high tide.

“There’s going to come a time where our outfalls and our drainage systems could get backed up permanently with sea-level rise flooding,” said Freudenberg.

If combined sewer outfalls are submerged, the system basically can’t flush and — if tides are high enough — sea water can push back up into the system and flood the city’s streets.

That phenomenon — tidal flooding — is already an issue for some of the city’s low-lying coastal communities. In neighborhoods like Jamaica Bay in Queens, sewers overflow several times a month, leaving residents in knee-high salt water, damaging homes and vehicles.

One proposed fix is to equip combined sewer outfalls with “tidal gates” — flaps that close when combined sewer outfalls are submerged and open back up when the tide recedes. But if sea levels always remain above the flaps, the sewage system could be permanently flooded.

“That’s a very real threat down the line,” Freudenberg said.

A Threat to the City’s Rail System

The Metro-North Hudson Rail line carried more than 87 million passengers in 2017. (Wikimedia Commons)

New York City’s public transit system is just beginning to feel the effects of climate change. The partial shutdown of the L subway line for post-Sandy repairs, which started in April, is a serious disruption for the line’s 400,000 daily commuters.

But this could just be the start of the city’s climate-induced transit woes. As sea levels rise, major railways could be affected as well.

Several portions of the Metro-North Hudson railway, which carried more than 86 million passengers in 2017, could be underwater by the time sea levels rise more than three feet, according to a study by the Regional Plan Association.

“We’re going to have to look at how we elevate rail infrastructure in places that are particularly low-lying,” said Freudenberg. “That could impact ridership into the city and the gains we’ve made getting people out of cars and onto mass transit.”

“Imagine trying to run an airport where you’re trying to land planes with flooded runways.”

Aerial view of LaGuardia Airport. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Another major transportation hub that could suffer is LaGuardia Airport.

The Regional Plan Association estimates that just one foot of sea level rise could disrupt air traffic at the Queens airport, built in the 1930s, long before climate change was on the map for city planners.

And that’s right around the corner. Sea levels could increase by 0.83 feet by the end of the 2020s, per city estimates.

Beyond three feet of sea level rise, half of the airport could be permanently flooded, potentially disrupting more than 28 million passengers every year, the study warned.

“You can keep water off of LaGuardia airport up to about five feet, but beyond that it’s going to face continual flooding,” said Freudenberg. “Imagine trying to run an airport where you’re trying to land planes with flooded runways.”

John F. Kennedy Airport is not at risk of flooding from rising seas, Freudenberg said.

People admire East River Park’s native plant species and birds during a nature walk led by the Lower East Side Ecology Center in Manhattan. (Gaspard Le Dem)

Resilience Please, But Not in My Backyard

By Gaspard Le Dem

Preparing New York City for climate change will be a monumental task. The city will need money, time, expertise and a whole lot of political will. Officials will also face the considerable challenge of getting communities to support major resiliency efforts.

The Not In My Backyard mentality — NIMBYism — is a hurdle that the city will have to overcome as it takes on projects like the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project.

The $1.45 billion seawall project to protect Manhattan’s Lower East Side from flooding and rising sea levels has been met with fierce opposition from local residents who say it will disrupt their community by destroying East River Park.

The city plans to raise the park to rebuild it eight feet up so it can act as flood protection in the event of future storms.

While many Lower East Side residents say they recognize the need to protect the neighborhood, which experienced severe flooding during Hurricane Sandy, they also insist that protection should not come at a cost to their community.

Robert Freudenberg, vice-president of energy and environment at the Regional Plan Association, said the issue only comes up when city officials fail to do their job.

“NIMBYism becomes a process if there’s not good communication between the city and the neighborhood,” said Freudenberg.

But creating a more climate-resilient city while meeting a community’s needs is a difficult task, said Timon McPhearson, director of the New School’s Urban Systems Lab.

“New York City is a very heterogeneous place, and people have very different ideas about how they want their communities to develop over time,” said McPhearson. “There’s a challenge of meeting high-level citywide planning goals and doing them in a way that communities not just accept them, but co-design them and have agency in that design making.”

McPhearson said that city agencies can only benefit from involving residents in the planning process.

“Communities know their neighborhoods,” said McPhearson. “So communities have important knowledge about what kind of investments would be most effective, and where they need to be placed. And that’s going to be different in East Harlem than it is in Red Hook.”

By Liam Quigley

When summer temperatures inch into the 90s and humidity intensifies the misery, Bertone Commissiong, a 93-year-old resident of the Conlon-Lihfe housing complex in Jamaica, Queens, has a ready solution: He turns on his air conditioner.

More than 60,000 of his fellow elderly residents in public housing aren’t so lucky — and with climate changes pushing the mercury into dangerous territory on many summer days, they are increasingly at risk.

Average daily maximum temperatures across New York City have risen steadily over the last few decades. From 1900 to 2013, they rose by 2 degrees in Central Park, and since 1970, they have risen by 2 degrees at JFK Airport and almost 3 degrees at LaGuardia, according to the New York City Panel on Climate Change’s 2019 report.

Going forward, without climate adaptation, heat waves are likely to get longer, hotter and more sporadic, the city’s OneNYC 2050 report predicts: “At the same time, greater dependence on air conditioning will place heightened demand on the city’s electrical grid, increasing the chances of larger and longer blackouts in summer months and leading to infrastructure outages and spoiled food and medicine stocks. “

Children play next to an open fire hydrant in the Bronx. (Liam Quigley)

This March was the second hottest on record globally, and the warming trend is likely to continue. The number of people dying because of heat in the city could rise to several thousand by 2080 if more action isn’t taken, according to a Columbia University study.

While the city is taking steps to mitigate heat waves in the long term, getting people cool in the meantime will have to be a priority.

Michael Schmeltz, a doctor and expert in health sciences, says that global warming is increasing the frequency and intensity of heat waves — and that extreme heat waves will show up earlier in the season.

“Heat waves in the early summer catch people off guard, so you’re more likely to see hospitalizations or mortality with these events. People may not have installed their air conditioners yet,” he said.

Cooling centers are opened up across the city during heat waves, but getting people into them in the first place is a challenge, Schmeltz said.

“We can’t just say we’ve opened cooling centers and leave it at that. We need to take a more active approach in getting them to cooling centers,” he added.

The city is investing $930,000 to do just that. The two-year pilot “Be A Buddy” program is underway uptown and in the Bronx, in partnership with THE POINT Community Development Corporation.

Organizers hope to recruit people to check in on elderly and at risk neighbors during heat waves. Maps showing where those deemed most at risk live focus on areas largely populated by those with little means and often those of color.

Jalisa Gilmore works as a research analyst at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, part of the organizing body that published a report on New York City’s ability to achieve climate resiliency. She says they are pushing for more funding to expand the program to other parts of the city.

“The program is designed to prepare communities for future climate emergencies, with a focus on extreme heat,” she said.

Gilmore said that taller buildings, like the 13-story NYCHA complex in Jamaica, can become scorching in the summer. “The higher you go, the hotter it’s gonna be. So it’s really a concern, especially the barriers to air conditioning cost,” she added.

More households getting cash assistance to help keep cool across the state.

New York State has doubled the cash on hand to $6 million in 2019 after applications from residents to get help cooling their homes surged during the hot summer of 2018.

Other efforts to cool things down are underway across the city. Officials announced in April that more than 10 million square feet of roofs have now been painted as part of the Cool Roofs NYC program. More than 1 million trees also have been planted since 2007 to help absorb the heat captured in the city’s concrete jungle.

While there is no rule requiring landlords to keep apartments cool, there is state money on hand for people who have a health condition that is worsened by heat and humidity. The cash on hand for that program has doubled this year to $6 million after a surge in requests for help during last summer’s miserable heat waves.

Commissiong pays $120 in extra rent a year to NYCHA for the privilege of having an air conditioner in his Jamaica apartment. And while it means he doesn’t have to seek out a cooling center as the thermometer rises, he is heated in opposition to the added rent.

“It’s time to freeze the rent,” he said. “They should put it in all the buildings.”

By Reginald Blake

For a long time, New York City and water have experienced a fruitful relationship. For hundreds of years, its rivers and harbors have worked to the city’s advantage, bringing swift transportation, trade, recreation and pleasant spring and summer temperatures to the area.

Those days are largely over, and the days to come threaten to be far from pleasant because of climate change and its effects on New York’s geography and weather patterns. Higher seas, unpredictable storm surges, more intense hurricanes and repeat flooding spell big trouble for coastal New Yorkers.

Sea levels around the five boroughs have risen by nearly a foot over the past century. The increase in temperature is melting glaciers and producing life-altering storms. The Hudson River is estimated to rise by 1.5 to 2 feet by 2050, directly affecting the low-lying areas of Staten Island, Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan.

Rubble caused by Sandy is still prevalent at this Brighton Beach house. (Reginald Blake)

Among the many coastal cities in the world, New York City, surrounded by water on three sides, is one of the most vulnerable to impacts of climate change.

Hassan Ahmad, 45, has only known one neighborhood since he moved to Brooklyn from Pakistan 38 years ago: Brighton Beach. Brighton Beach is an arm’s length away from the Atlantic Ocean and is particularly likely to be hit by flooding. After Hurricane Sandy, Ahmad realized it might be time to go.

“Sandy really screwed us over. I told my wife, I said, ‘Look, I don’t know if we can do this.’”

“Sandy really screwed us over,” said Ahmad, who lives with his wife, his mom, and his three young children. His entire basement, where his mother lived, was flooded, and he went without electricity for weeks. The damage to the house was followed by the damage to his wallet — his flood insurance almost doubled after Sandy.

“I told my wife, I said, ‘Look, I don’t know if we can do this.’”

Elizabeth Malone is the program manager for insurance and resiliency at Neighborhood Housing services of Brooklyn, a nonprofit that helps low-income families navigate the process of buying a home. After Hurricane Sandy, Malone worked in Brighton Beach extensively, catering to the largely immigrant community reeling from rising flood insurance costs.

“You see a lot of older families who have been there generationally,” said Malone. “And many new immigrants who are also new homeowners. Those families tend to invest heavily in their homes, and then pass them along to their children. For many immigrant families,

she said, “the home is your entire financial life.”

The threat of flooding isn’t going unnoticed, but proposed solutions have been controversial and costly. Hurricane Sandy cost the city a whopping $19 billion; efforts to protect the city from future storm surges are likely to be at least as expensive (the current projection from the de Blasio administration is $20 billion). According to the Lower Manhattan Resilience survey, 37 percent of lower Manhattan will be at risk for storm surges by 2050.

“We don’t debate global warming in New York City. Not anymore,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio in a post in New York Magazine. “The only question is where to build the barriers to protect us from rising seas and the inevitable next storm, and how fast we can build them.”

While solutions to rising sea levels across the five boroughs are being proposed and debated, some residents in coastal areas of the city are making their own plans. Dante McKie, 22, lives in the Coney Island Houses, and the threat of flooding constantly has him worried. “First chance I get, I’m out, my family can’t manage another Sandy.”

Vickitora Jean-Louis has lived in Far Rockaway, Queens, for all of her 17 years. After Hurricane Sandy, her streets and basement were flooded, and she had no electricity for three weeks. “Immediately I realized that staying in New York was no longer an option for me,” she said. A senior at the High School of Fashion Industries, Jean-Louis knows that events like Sandy are likely to occur again, and she doesn’t want anything to do with it. “My friends and I used to talk about it all the time. The signs of climate change are everywhere.”

Climate change is indeed a global issue, but in New York City, it is pushing out the door some of the very people who make the city what it is.

Rebels With a Cause

A new generation of climate change activists has more radical politics than the environmentalists who came before them.

Backyard Solutions

With city initiatives either failing or not being implemented, schools, individuals and businesses are creating their own solutions to combat climate change.

By Jaya Sundaresh

The protesters lay on Centre Street in Manhattan, like scattered matches. They lay with their heads pillowed on each others’ bodies, faces shielded from the late-morning sun by their hands.

The scene? A “die-in” to dramatize the need for immediate action to fight climate change.

Supporters yelled out words of encouragement and gratitude to the protesters who were lying on the ground. A large banner that read “declare climate emergency” was hoisted, and NYPD speakers blared a warning to those lying in the street: Stop obstructing traffic, or face arrest.

One by one, the Extinction Rebellion protesters were arrested, their hands zip-tied behind them as they walked away to supportive cheers from the crowd. The Rev. Chelsea MacMillan, lying in the street, waiting to be arrested, began to sing: “We are the earth, we are the sea, we won’t stop rising ‘til we are free!”

A string of Extinction Rebellion protestors with linked arms block Centre Street, as NYPD looks on. (Jaya Sundaresh)

They are just some of the many activists who have taken a more radical approach to environmental organizing in recent years. Organizations protesting climate change have sprung up nationwide.

Some more activist organizations, like Sunrise Movement and Zero Hour, are explicitly led by young people, while others, like Extinction Rebellion and 350.org, are led by people of all ages. But all share a commitment to a more radical politics than traditional environmental organizations have followed in the past.

“If you look at the science, the science is saying that if we don’t get our act together, we’re looking at creating a climate that would likely topple our civilization as we know it,” said John Johanson, one of the 61 Extinction Rebellion protesters arrested that day.

“We’re trying to ensure the survival of humanity on this planet,” said MacMillan, echoing Johanson.

“If you look at the science, the science is saying that if we don’t get our act together, we’re looking at creating a climate that would likely topple our civilization as we know it.”

The demands of these organizations are scaled to meet the immensity of the challenge of confronting climate change.

Extinction Rebellion has the ambitious goal of ending carbon emissions by 2025. Zero Hour has a 2040 deadline for a full transition away from fossil fuels. And Sunrise Movement has championed the Green New Deal, which calls for a 10-year national mobilization to transition to renewability. The Paris Climate Agreement calls for zero carbon emissions worldwide by 2050, the year that climate experts say may be the point of no return on climate disaster.

A key tenet of most climate activist groups is that the most marginalized populations need to be at the forefront of this “just transition,” because they are the least likely to have caused climate change and the most likely to be harmed from it. This includes “black people, Indigenous people, people of color and poor communities,” according to Extinction Rebellion’s website.

What sets these movements apart from older, more traditional environmental movements?

For one, older groups such as the Nature Conservancy and the Environmental Defense Fund have a more top-down structure and are less grassroots in origin. They have more business and government ties, and in some cases, have been linked to fossil fuel producers. And their priorities are less laser-focused on climate change than current movements are, said Miles Goodrich, New York State director for Sunrise Movement.

“For the past few decades, they’ve been focused on corporate responsibility or land conservation, that sort of thing,” he said. Climate change, the most pressing environmental issue of our time, according to these activists, doesn’t rank nearly as highly as it should.

Indeed, the Environmental Defense Fund’s website features a page called “making it profitable to protect nature,” describing why the environmental movement should work with corporate interests to combat environmental ills.

It is a far cry from the anti-business ideology of Extinction Rebellion, whose protesters chanted “let the corporations burn” as they were getting arrested.

Most of the current crop of environmental activists were harvested from other social justice movements, not from older environmental movements.

“They’re coming from racial justice movements, they’re coming from Occupy Wall Street.” explained Goodrich. “It’s an intersectional movement that draws from very different threads.”

Millennials and their Generation Z siblings are powering this movement. The 29-year-old congresswoman from Queens, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, has famously championed the Green New Deal, propelling the issue to the forefront of the national conversation. Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old Swedish schoolgirl, has made international headlines for her “climate strike.” Schoolchildren across the world followed Thunberg’s lead and skipped school to protest climate change on March 15.

“Our politics were really forged in times of crisis, from 9/11 and the wars that were sold to us under deception by our government, to the housing crisis and the financial recession, to the election of a president who campaigned as a white supremacist,” said Goodrich, who is 26.

Ivy Jaguzny, 17, a national leader with Zero Hour, a youth-led anti-climate change organization, used to work with an organization called Citizen Climate Lobby, but she felt uncomfortable being the only young person in the room. Besides, she wanted to do more than just reach across the aisle. “I attended a CCL meeting where we learned to talk to climate deniers, and I think we are more unapologetic than that,” said Jaguzny, citing the direct actions that Zero Hour carries out.

A director of a more traditional statewide environmental organization, who asked not to be identified to allow a more honest assessment, was full of praise for both the younger generation and the more militant organizing tactics they were ushering in.

“How many years now has it been a line coming from elected officials, or from safe green organizations, that you need to protect the climate because the next generation depends on it?” she asked. “Now we have the next generation, that’s going to be very much so impacted by climate change, telling us to act. There’s something great about hearing from Gen Z about how they see climate change.”

Jaguzny echoed her. “The one thing that differentiates us from older generations is that we feel the personal weight of these issues, and we feel threatened.”

As Adele Fisch, 21, a protester at Extinction Rebellion, put it: “I’d like to have children or grandchildren someday, and I don’t want to bring children into a dying world.”

By Jose Cardoso

The City College of New York is one of many New York institutions testing initiatives to deal with climate change. CCNY architecture and engineering students designed and built a solar RoofPod atop the Spitzer School of Architecture that goes well beyond standard solar panels.

The 800-square-foot prototype pod, which resembles an airy stand-alone penthouse, uses sun, air and water for heating, cooling and lighting, and produces all the energy it needs plus surplus for the building below. The pod was designed to be installed on the roofs of commercial or residential buildings in high-density urban centers.

Professor Christian Volkmann, who supervised the project, said the pod also uses “smart house” technology to use energy more efficiently. Rather than automatically turn on the air conditioning on a hot day, the technology might instead lower the blinds or open windows. “The system understands that lowering humidity would be important or lowering CO2 levels would be important,” Volkmann said.

If Volkmann had his way, every building in New York and other urban areas would have its own roof pod. “The city has a huge advantage of being less vulnerable by having back up power on its roofs,” he said. Extensive terraces also absorb storm water runoff and protect against the heat island effect.

The New School’s University Center is leading the way in setting green technology standards alongside building practices in New York City. (Jose Cardoso)

Color It Green

The vegetation-covered green rooftop at the New School’s University Center is only one of many features that won the building a gold LEED rating from the U.S. Building Green Council. A cogeneration plant on site produces up to 40 percent of the building’s electrical energy.

Rain collected on the roof, plus water from sinks, showers and washing machines is treated and distributed for reuse in toilets and the cooling tower and for irrigating the green roof. The system reduces the demand on city water by 74 percent and also reduces what the building discharges into city sewers.

Fourteen tanks for ice generated at night help cool the air in the daytime, cutting peak air conditioning requirements by 30 percent, according to the New School website. Green building strategies are documented throughout student spaces, and a course on sustainable urban construction is taught in the building.

New York builders may want to take note. In January 2017, San Francisco became the first American city to require all new construction projects to incorporate green roofs, solar or a combination of both on between 15 to 30 percent of their roof space.

“We put our compost in and it basically dehydrates all the organic materials and you have potable drinking water at the end.”

Saving the Earth one Carrot Top at a Time

Purslane, a catering service in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, advertises itself as New York’s first trash-free and carbon neutral caterer. Besides buying organic ingredients from local farms and wineries, it reduces its carbon footprint through a combination of recycling, composting, “upcycling” and reuse programs to process wastes.

The company, which caters weddings and events, and also partners with restaurants, notes that the typical wedding or event produces 400-600 pounds of garbage. Instead, it avoids single-use or non-recyclable plastics, composts, and has teamed with TerraCycle, a recycling firm that accepts items that can’t be processed by municipal recycling programs.

Purslane is a member of ZeroFoodPrint, a nonprofit that works with restaurants to teach the climate impact of different food, equipment and methods choices. At its new restaurant in Gowanus, the company is adopting a new earth-friendly method. “We’re looking at having our own composter and water extractor in the kitchen,” said events coordinator Ari Rizzo. “We put our compost in and it basically dehydrates all the organic materials and you have potable drinking water at the end.”

Composting will soon become a hot topic in New York. One bill in the Climate Mobilization Act signed in April by Mayor Bill de Blasio makes organic recycling mandatory city-wide. The goal is to ensure a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and overall garbage loads by the year 2030.

Credits

A project of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

Reporters

Reginald Blake

Jose Cardoso

Gaspard Le Dem

Charlie May

Liam Quigley

Jaya Sundaresh

Project Manager

Gaspard Le Dem

Web Producer

Liam Quigley

Faculty Advisers

Judith Watson

Christine McKenna